Scotland's forgotten king

by Matthew Hammond,

If you pick up any popular history of Scotland’s kings and queens, chances are you will find no mention of Edward Balliol. Yet Edward was crowned king of Scots at Scone on 24 September, 1332, enthroned by the earl of Fife and anointed by the bishop of Dunkeld, with a bevy of worthies in attendance. Edward certainly had a reasonable claim to the kingship. His father, John Balliol, had been inaugurated at Scone in 1292 and reigned until 1296, when King Edward I invaded and stripped King John of his royal insignia, making him an ‘empty coat’ (‘Toom Tabard’ in Scots). Yet Balliol almost certainly had the superior claim to the Scots throne after the deaths of Alexander III (1286) and Margaret of Norway (1290), and Scottish patriots like William Wallace continued fighting in John’s name for years after his humiliating defeat.

The seal of Edward Balliol as king of Scots

Edward, John’s son, was already about 49 years old when he was crowned king of Scots, having spent a life of privilege and luxury, growing up in the courts of the future Edward II as well as his cousin John de Warenne, earl of Surrey. After his father’s death in 1314, Edward succeeded to the Balliol estates in France, centred on the château of Hélicourt in Vimeu in Picardy. Edward’s potential claim to the Scottish kingship became the focus for a group of nobles disinherited by Robert I. Some of these had been Scottish families who fled the kingdom, Balliol adherents and Bruce enemies like the MacDougalls of Lorn in Argyll, or the MacDowalls in Galloway. Chief among these was David of Strathbogie, earl of Atholl. The majority of the Disinherited were nobles based in England who lost their Scottish lands. Most of these men were based in northern England, men like Gilbert de Umfraville of Prudhoe, former earl of Angus, and Henry Percy, lord of Alnwick, who had lost lands in Galloway and Angus. Probably the most tenuous claim was that of Henry de Beaumont, a knight in the English royal household who claimed the earldom of Buchan by right of his wife, Alice Comyn.

Reverse of King Edward Balliol's seal

After the death of King Robert in 1329 and the rise to personal rule of King Edward III of England the following year, the Disinherited began agitating seriously to try to stake their claims to the Scottish lands, through military action, and all in the name of King Edward Balliol. Beaumont and Strathbogie were the chief movers behind this, and with Balliol’s go-ahead, and the approval of Edward III, they readied for an invasion in the summer of 1332. They got lucky in that the much-respected regent of Scotland (David II was only eight), Thomas Randolph, earl of Moray, died of some physical malady shortly before the invasion was to take place. With a force of some two or three thousand men, Edward Balliol landed at Kinghorn on 6 August and immediately toward Scone and coronation. They met the Bruce side, led now by Donald, earl of Mar, at Dupplin Moor on 11 August, where Balliol was victorious, aided by the treachery of William Murray of Tullibardine, a local adherent to David Strathbogie, earl of Atholl. Patrick, earl of March, moved to relieve the Bruce army in Perth, but was cut off by Sir Eustace Maxwell of Caerlaverock. The earls of Fife and Strathearn, feeling that their formerly pre-eminent position had been thwarted by new men like Douglas and Randolph, threw their lot in behind Edward Balliol. Duncan, earl of Fife, played his traditional role in the inauguration ceremony at Scone, on 24 September. Another Atholl man, William Sinclair, bishop of Dunkeld, anointed the king with holy oil, in only the second time this ritual had been carried out in Scotland. (The pope finally gave his approval to coronation and unction in 1328.) Edward Balliol was the duly crowned king of Scotland.

Edward Balliol's charters, in the PoMS database

Edward’s moment in the sun was not to last long. Balliol’s charters reveal the difficulties he faced in trying to reward his followers with gifts of land. Readers can explore Edward’s acts now that 34 of his documents, acting as king of Scots, have now been added to the People of Medieval Scotland database. Readers can find these by entering 1/56 into the search box and going to the Sources result option. The documents have also been calendared, and are available here. We see in document 1/56/2, as early as October 1332, Edward rewarding his knight Thomas Uhtred with lands of Bunkle in Berwickshire, lands which had been forfeited by the knight John Stewart, a Bruce supporter. But the place-date and the witness list of this charter belie the fact that Balliol was already struggling. He had set up base in Roxburgh, a defensible castle near the border, and with the exception of the earl of Fife, the men at his court were mainly the Disinherited he had started out with, men like Henry Beaumont, now titled earl of Buchan, David of Strathbogie and Gilbert de Umfraville reprising their hereditary roles as earls of Atholl and Angus, respectively, other English Disinherited, Richard Talbot and Henry Ferrers, and Balliol-supporting Scottish knights, Alexander de Mowbray and Eustace Maxwell. Edward’s base of support was still shallow. The following month, November 1332, Balliol succumbed to an extraordinary arrangement with King Edward III, who had decided to capitalize on Balliol’s perhaps unexpected early success. In exchange for the English king’s support, Balliol agreed to transfer 2,000 pounds’ worth of land from the kingdom of Scotland to the kingdom of England.

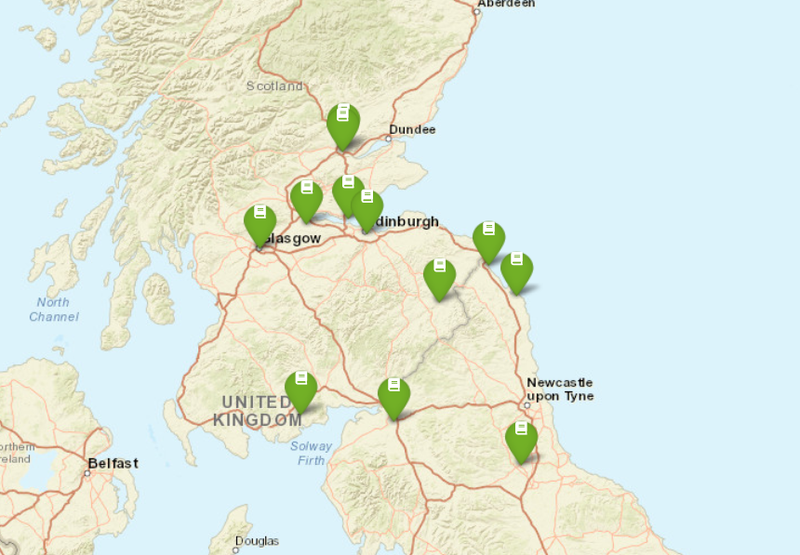

Map of the places where Edward Balliol's charters and letters were issued

Meanwhile, the Bruce side was gradually picking away at Balliol’s gains, with Sir Simon Fraser retaking Perth and Archibald Douglas and Thomas Randolph’s son John scoring a victory at Annan in December 1332, which sent Edward Balliol fleeing across the border to Carlisle and safety. By this time, Edward III was heavily invested in the mission, and the focus switched the following spring to the English siege of Berwick-upon-Tweed, one of the lands which Balliol had promised the English king. A large Scottish army of perhaps as many as 10,000 men attempted to relieve the garrison that July, but were routed on Halidon Hill. No fewer than five Scottish earls (Carrick, Atholl, Lennox, Ross and Sutherland) died in the battle, as well as the commander, Archibald Douglas. With the military force of Edward III behind him, Balliol was able to hold parliaments in Perth in October 1333 and February 1334, attended by the great and good of the kingdom (Documents 1/56/7-10 stem from this second assembly). Edward Balliol was able to continue distributing the spoils of war to his followers, as his charters reveal, and this was key to the strategy of retaking various castles. He regained the Bruce castle of Lochmaben by giving Henry Percy, lord of Alnwick, title to the lordship of Annandale and Moffatdale in July 1333: Percy had to retake the castle by force (1/56/6 and 14). The transfer of most of southern Scotland to the kingdom of England was finalized at Newcastle-upon-Tyne in June 1334, when Balliol renewed his homage to the king. The entire sheriffdoms of Berwick, Roxburgh, Selkirk, Peebles, Dumfries, and Edinburgh including the constabularies of Haddington and Linlithgow were to become part of England henceforth (1/56/13). The map below showing the places where Edward Balliol’s documents were issued largely reflects this period in 1333 and 1334 when he attempted to hold on to his English-backed conquest (see 1/56/5-17). Most of this activity took place in Edinburgh and Roxburgh, but he did make it to Glasgow, where he renewed a charter of his father King John (1/56/17).

What followed was several years of intense fighting between the Bruce and Balliol sides, with the Bruces holding on to the key castles of Kildrummy in Mar and Dumbarton on the Clyde. Balliol. The leaders of the Bruce side were now John Randolph, who went to France to secure their support, and Andrew Murray, who targeted and killed David Strathbogie at the battle of Culblean in November 1335. The Balliol side harried the Stewart lands in the Firth of Clyde, and a major indenture was made with John of Islay, lord of the Isles, in 1336, which would transfer ownership of Kintyre and Knapdale from the Stewarts to the MacDonalds (1/56/19). Edward III’s army concentrated on holding Perth and striking out from there, but Murray attacked English garrisons across the country in 1337 and 1338. Murray died in 1338, but Robert Stewart regained Perth the following year. With Edinburgh secured by William Douglas in 1341, David II returned from exile in France and the dream of Balliol and the Disinherited was effectively stymied.

We have a long lacuna in Balliol’s charters between 1339 and around 1347. After the defeat of the Scots and the capture of David II at the battle of Neville’s Cross in 1346, there were less ambitious attempts to revive the cause. Balliol gained the support of Henry Percy and either 30 knights or 100 men-at-arms (1/56/24), and focused his efforts on holding the old Balliol lordship of Galloway, where we have him rewarding (either retroactively or speculatively) his valet William of Auldburgh for holding various lands in Galloway, in 1348 and 1352 (1/56/25-28). Edward III preferred to pressure the captive David II into becoming a vassal king over continuing the quixotic mission to elevate Edward Balliol. In 1355, the French sent military support to the Scots, who retook Berwick soon thereafter. Edward III brought an army north in January 1356, razing Edinburgh in the ‘Burnt Candlemas’. At Roxburgh on 20 January, 1356, Edward Balliol resigned all his rights and claims to the kingdom of Scotland to Edward III, including his golden crown, in return for an annual allowance of 2,000 pounds (1/56/29-34). The dream of Balliol kingship was well and truly finished. Edward lived another eight years, dying near Doncaster in 1364. He ended his life like he began it, on the English dole.

If you want to learn more about the life of Edward Balliol, may we recommend Amanda Beam’s The Balliol Dynasty, 1210-1364 (Edinburgh, 2008). Beam’s appendix of Edward’s acts formed the basis of our calendar of his documents as king, but her Appendix D goes much farther, including charters and letters of Edward Balliol before and after his kingship, as well as ‘lost acts’ known from other sources.

Written by Matthew Hammond, 19 July 2019. For a pdf of this short feature, click here. For the calendar of Edward Balliol's acts as king, click here.

<< Go back to The COTR blog home | < Previous post | Next post >